It is in Rajasthan that I am reminded mostly of the Australian outback: stones change colour with the starkness of a Sydney Noland portrait. A colour both brutal and subtle. A surreal not quiet desolate scene. Arid, untidy, a mysterium of colour palette knifed across shimmering cornfields of northern state cities in block colour: Agra is red, Jaisalmer yellow,Jodhpur blue, Udaipur white, Jaipur is pink, while Mandawa and Nawalgarh are polychromies.

Contrast this with the colour anarchy of the soujthern states.

In Rajasthan I think It is Red.

The red of passion, of “I am leaving you” agony, of smitten hearts, perhaps a Westerner I am fueled by images of artists living on art and love.

Yet, as women float by I am reminded that in the past kapot or gray in ancient poetic art. Little mention of red with humans in their astra, vastra, abhushan, sana or vihara aspects. In earlier Indian art Devatas, apsaras and yakshas possess a gaur or fair complexion.

No women is dressed in or coloured in the red hue of passion.

It is now red is considered the colour of romance or shringara, the hue of fertility and auspiciousness.

We must go back to the mediaeval Sur Sagar text o find women expected to wear red at the birth of a son of Nanda. They anointed forehead and smear parting of their hair with red with a dash of sinhur.

Perhaps it is in the 7th century Harshacharitra text we have the earliest classification of red. In the red on flowers and on rooster comb, pigeons feet.

Buddhists and Jain were the first to use red in iconography texts: Jain siddhas and Buddhist Amitabha are required to be red and red is used in the tantric mandala. For Buddhist red was the colour of passion, hatred, subjugation fire aggregated sensation.

Yet red has no importance in the mural of Ajunta, or in manuscripts. Even the romantic old Gujurati scroll of 1493, the Vasanta Vilasa sparely uses red.

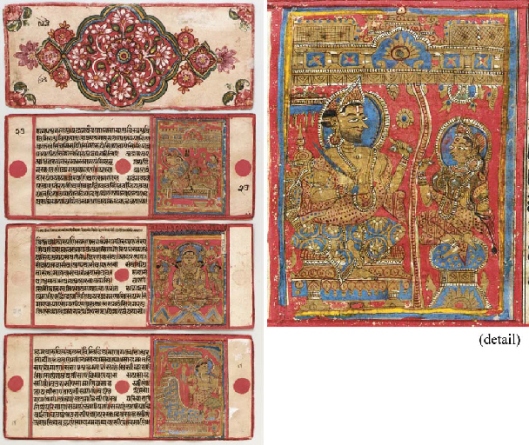

It is in pre Mughal and in Mughal & Rajasthani ateliers of the 16 – 18th century that red is important.

At this time paintings and manuscripts were symbols of power. It is staggered to realise that manuscripts, books and paintings were often parts of a dowry. A Bijapuri Chronicle reports two thousand manuscripts from a Deccani royal library were given as dowry for the daughter of Bijapuri ruler Ibrakim ‘Adil Shah II and Mughal prince Daniyal.

At times paintings exchanged were to assess an adversary’s character in efforts to press for political advantage. The above Ibrahim received a portrait from Jahangir personally inscribed verses and a ruby along with an authorisation to take territory from a rival Deccani ruler.

Similarly Sah Jahan forced a deal that compromised a Deccani ruer of Golkonda in 1635 and sealed the deal with a portrait of himself in gem encrusted frame. Mughals rulers valued MSS as prizes of war and the many Rajasthani princes obliged to stay in Mughal courts were probably influenced by Mughal mural and miniature painting.

In this time of art equals power Royal sanas were red to depict power, standing of a noble: Mughal and Rajput costume, the palaces and havelis, their tents, awnings . Soon, married woman wore red chuda (bangles) bindi (forehead mark) and nath or nose ring were ornaments or suhag of a married woman. Red on the chunri or odhni of Rajput women indicate status or marriage, although not initially necessary, because early Rajput society used the veil to suggest romantic nuances or feelings.

By the 17th century, the Mughal influence in North India had spread bhakti movements like the riti kavyaij performing arts.

Perhaps red was highlighted because of the Bhafgavata Purana, Gita Purana. Rasikapriya and Sat Sai.

In Bhagavata Purana from Bikaner Krisna is cut out behind a red backdrop. Around Bundelkhand is painted a solid red backdrop. It is later that artists began to bleed art on to tree trunks as patrons sought to depict the moods of the nayika and nayika.

Bihari in his Sat sai evokes celebration of a nayika with rosy feet – like a red dhupahriiya flower blossoming with each step she takes. Called mahavaralaktaka, the ornament is also mentioned in Sanskrit poetry.

A nayika’s lips increasingly red as are hands feet. Red became the colour of beauty also of love, lust romance and amorous pleasures.

The art o applying alaktaka, red die to soles and sides of feet is a well developed alamkara or adornment of nayika women and for men.

Tree juice Alaktaka was essential for a womans shringara – especially for a nayika. Artists would ‘lab me liaf’ add red on the lips to show a nayikas portrait was complete.

In a poetic description, the Nakhshikh Varnan, from her tresses to her toes, forehead, lips gums hands and feet , a nayika is suffused with hues of red, especially at festivals. Eating of pan – became common for courtesans – even those who did not eat it would colour their feet .

An abundance of red cloth filled Medieval india. In the Kapar Kutuhal we read of lakharas or dye of laquer that adds “a million fold lustre”.

Now even the seasons have their own shade of red:

| Chaitra/March-April jyestha/May June |

Rose pink |

| Bhadrapad /july -august | Malaygiri or red sandalwood |

| Ashvin /sept -oct | Kasumal pink red |

| Kartik nov dec | Sindhuria orange red |

| Magh jan-feb | Kesariya or saffron, ul-e-anar pomegranate |

So now in Rajasthan we find the red of fertility and auspiciousness. The nuanced reds is of love and romance.

Other concerns however invade my mind: There are maany Rajasthan tradition suffering under the onslaught of mass produced art, and marketed music…Check out th Efforts to save the endangered oral traditions of Rajasthan: Vishesh Kothari.

Sources:

The material for this post is primariy from material of Aesthetics of red in Rajasthani paintings by Naval Krisna